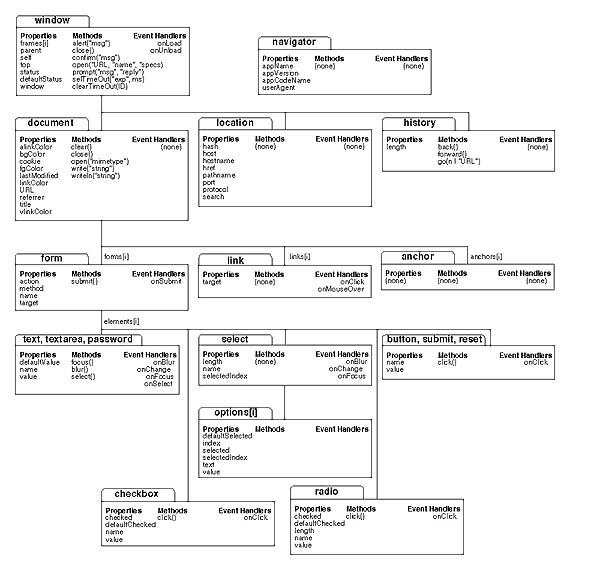

his chapter describes JavaScript objects in Navigator and how to use them. These client-side JavaScript objects are sometimes referred to as Navigator objects, to distinguish them from LiveWire objects or user-defined objects.

his chapter describes JavaScript objects in Navigator and how to use them. These client-side JavaScript objects are sometimes referred to as Navigator objects, to distinguish them from LiveWire objects or user-defined objects.

In this hierarchy, an object's "descendants" are properties of the object. For example, a form named form1 is an object as well as a property of document, and is referred to as document.form1. Every page has the following objects:

For example, the following refers to the value property of a text field named text1 in a form named myform in the current document.

document.myform.text1.value.

simple.html that contains the following HTML:

<HEAD><TITLE>A Simple Document</TITLE>As you saw in the previous chapter, JavaScript uses the following object notation:

<SCRIPT>

function update(form) {

alert("Form being updated")

</SCRIPT>

</HEAD>

<BODY>

<FORM NAME="myform" ACTION="foo.cgi" METHOD="get" >Enter a value:

<INPUT TYPE="text" NAME="text1" VALUE="blahblah" SIZE=20 >

Check if you want:

<INPUT TYPE="checkbox" NAME="Check1" CHECKED

onClick="update(this.form)"> Option #1

<P>

<INPUT TYPE="button" NAME="button1" VALUE="Press Me"

onClick="update(this.form)">

</FORM>

</BODY>

objectName.propertyNameSo, given the preceding HTML example, the basic objects would have properties like those shown here:

| Property |

Value

|

document.title |

"A Simple Document" |

document.fgColor |

#000000 |

document.bgColor |

#ffffff |

location.href |

"http://www.sampson.com/samples/simple.html" |

history.length |

7 |

|

|---|

Notice that the value of document.title reflects the value specified in the TITLE tag. The values for document.fgColor (the color of text) and document.bgColor (the background color) were not set in the HTML, so they are based on the default values specified in the Navigator Options|General Preferences dialog box.

Because there is a form in the document, there is also a Form object called myform (based on the form's NAME attribute) that has child objects for the checkbox and the button. Each of these objects has a name based on the NAME attribute of the HTML tag that defines it, as follows:

These are the full

names of the objects,

based on the

Navigator object

hierarchy.

http://www.sampson.com/samples/foo.cgi, the URL to which the form is submitted.

<FORM NAME="statform">These form elements are reflected as JavaScript objects that you can use after the form is defined: document.statform.userName and document.statform.Age. For example, you could display the value of these objects in a script after defining the form:

<INPUT TYPE = "text" name = "userName" size = 20>

<INPUT TYPE = "text" name = "Age" size = 3>

<SCRIPT>However, if you tried to do this before the form definition (above it in the HTML page), you would get an error, because the objects don't exist yet in the Navigator. Likewise, once layout has occurred, setting a property value does not affect its value or appearance. For example, suppose you have a document title defined as follows:

document.write(document.statform.userName.value)

document.write(document.statform.Age.value)

</SCRIPT>

<TITLE>My JavaScript Page</TITLE>This is reflected in JavaScript as the value of document.title. Once the Navigator has displayed this in the title bar of the Navigator window, you cannot change the value in JavaScript. If you have the following script later in the page, it will not change the value of document.title, affect the appearance of the page, nor generate an error.

document.title = "The New Improved JavaScript Page"There are some important exceptions to this rule: you can update the value of form elements dynamically. For example, the following script defines a text field that initially displays the string "Starting Value." Each time you click the button, you add the text "...Updated!" to the value.

<FORM NAME="demoForm">This is a simple example of updating a form element after layout. Using event handlers, you can also change a few other properties after layout has completed, for example, document.bgcolor.

<INPUT TYPE="text" NAME="mytext" SIZE="40" VALUE="Starting Value">

<P><INPUT TYPE="button" VALUE="Click to Update Text Field"

onClick="document.demoForm.mytext.value += '...Updated!' ">

</FORM>

For more information on windows and frames, see Chapter 3, "Using windows and frames."The window object is the "parent" object for all other objects in Navigator. You can create multiple windows in a Navigator JavaScript application. A Frame object is defined by the FRAME tag in a FRAMESET document. Frame objects have the same properties and methods as window objects and differ only in the way they are displayed. The window object has numerous useful methods:

location = "http://home.netscape.com"You can use the status property to set the message in the status bar at the bottom of the client window; for more information, see "Using the status bar".

document object

Because its write and writeln methods generate HTML, the document object is one of the most useful Navigator objects. A page has only one document object.

The document object has a number of properties that reflect the colors of the background, text, and links in the page: bgColor, fgColor, linkColor, alinkColor, and vlinkColor. Other useful document properties include lastModified, the date the document was last modified, referrer, the previous URL the client visited, and URL, the URL of the document. The cookie property enables you to get and set cookie values; for more information, see "Using cookies".

The document object is the ancestor for all the Form, Link, and Anchor objects in the page.

form object

Each form in a document creates a Form object. Because a document can contain more than one form, Form objects are stored in an array called forms. The first form (topmost in the page) is forms[0], the second forms[1], and so on. In addition to referring to each form by name, you can refer to the first form in a document as

document.forms[0]

Likewise, the elements in a form, such as text fields, radio buttons, and so on, are stored in an elements array. So you could refer to the first element (regardless of what it is) in the first form as

document.forms[0].elements[0]

location and history objects

The location object has properties based on the current URL. For example, the hostname property is the server and domain name of the server hosting the document.

The history object contains a linked list of strings representing the last ten URLs the client has visited. Although you cannot directly access these values (for privacy reasons), you can redirect the client to any of them with the go method. For example, use

history.go(-2)

to load the URL that is two entries back in the client's history list. To reload the current page, use

history.go(0)

The history list is displayed in the Navigator Go menu.